|

|

Captain Marvin Creamer's Circumnavigation Without Instruments |

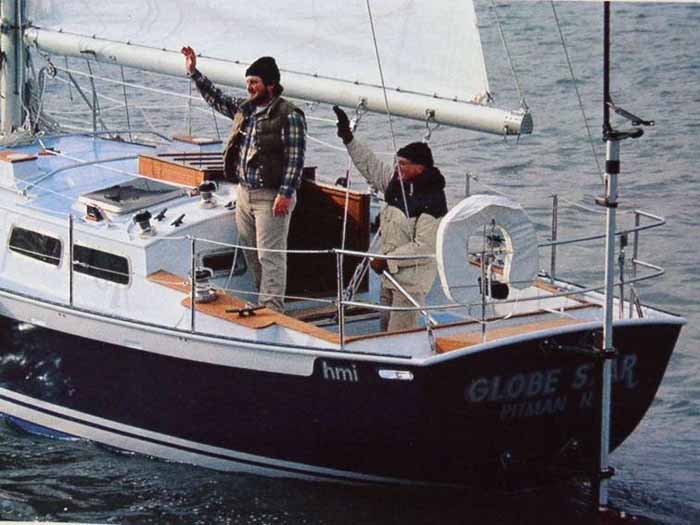

The Globe Star Voyage

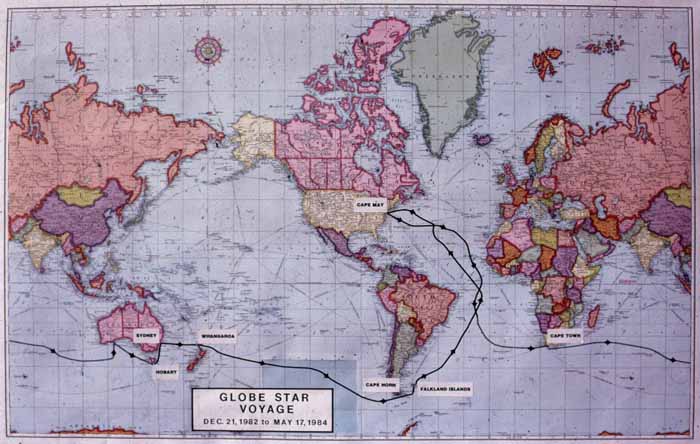

This map shows the route taken by Creamer on his circumnavigation without

instruments. Globe Star sailed to South Africa by way of Dakar, West Africa and Cape Town. From there, she sailed to Australia, New Zealand, Cape Horn, the Falkland Islands, by Cape Verdes

and Bermuda, finally ending at Cape May on May 17, 1984.

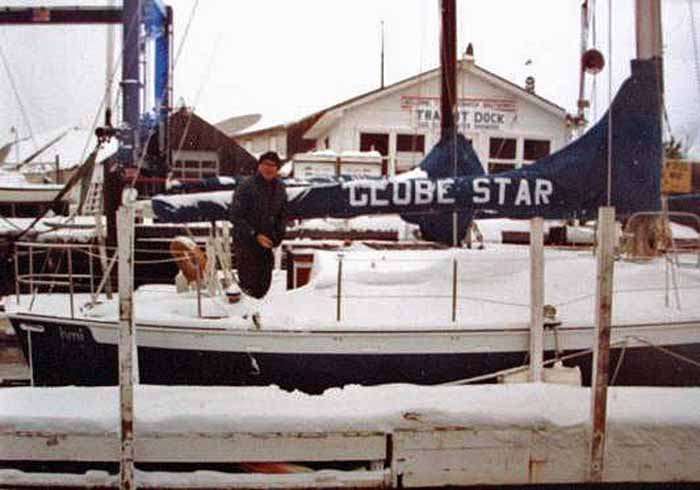

There was much work to do in preparing for the voyage. Delivery of the Globe Star was

promised by August, 1982, but it didn't arrive until December 1st, leaving very little time to get

the vessel ready and stash everything needed on board. Winter arrived early and snow had to be

cleared from the deck before any work could be done.

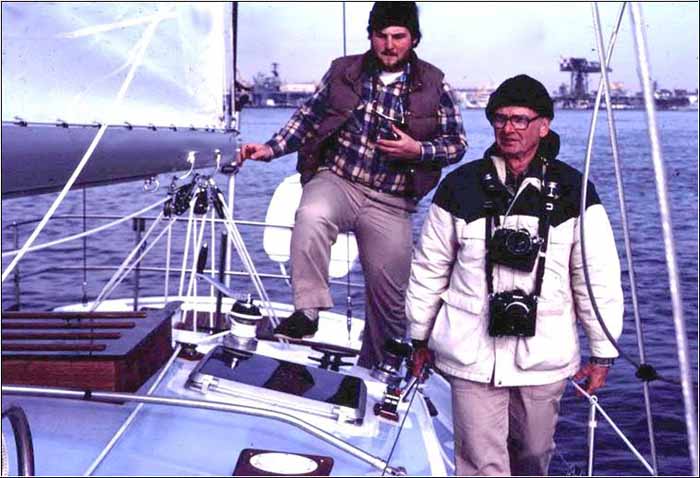

Marvin Creamer found crew to accompany him on different stages of his voyage, stocked food, fuel, water and other items including items

needed for possible emergencies. In addition to tools and spare parts, he included medicine, splints and even scalpels for performing minor operations.

No sextant or compass would guide him on his long journey — only stars, winds, water currents and occasional signs of life served as his guides.

With no normal navigational instruments, Marvin knew that there was a good possibility of his spending days or weeks on a raft or marooned on a

desert island awaiting rescue. Even the prospect of meeting death did not deter Creamer. His wife Blanche was also aware of the dangers but she

knew that this undertaking was a life-long ambition of her husband and she was not going to stand in his way.

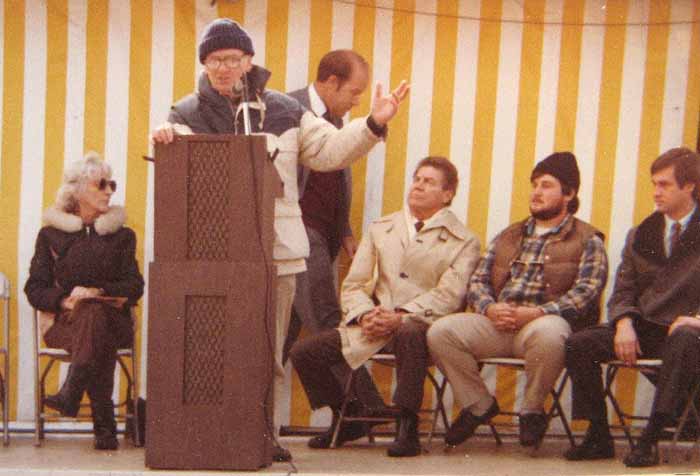

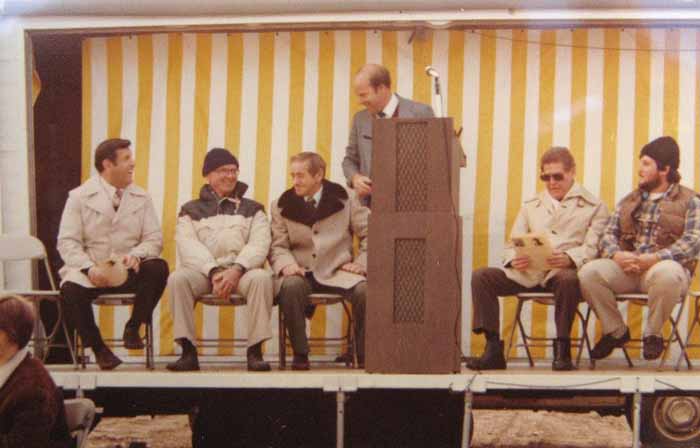

Globe Star's send-off took place on December 15, 1982 at Red Bank Park, NJ, on the Delaware

River opposite Philadelphia Airport. In spite of cold weather and snow on the ground, it was a media event with five television crews, a news

helicopter providing live coverage and reporters from wire services, press and radio. The marching band from nearby Gateway Regional High School

provided music and dignitaries, including a U.S. Congressman, gave speeches. Officials of Gloucester County Weights and Measures Department were

on hand to seal and notarize the compass, sextant, watch, and radio in a waterproof canvas

duffel bag, that was then stowed below deck. Only a specially made hourglass would be used on this voyage!

Few of those on hand for the send-off knew it, but the Globe Star would return to Cape May for a few more days of preparation -

without the press being on hand to interfere with work!

The first leg was to Cape Town, South Africa and Globe Star sailed a distance of 7800 nautical miles in 100 days.

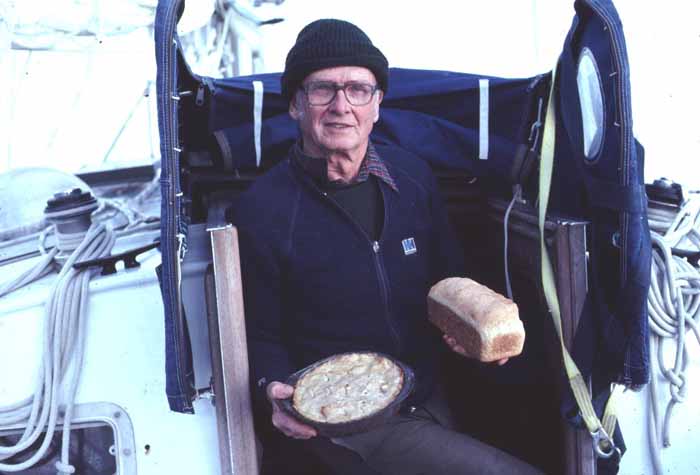

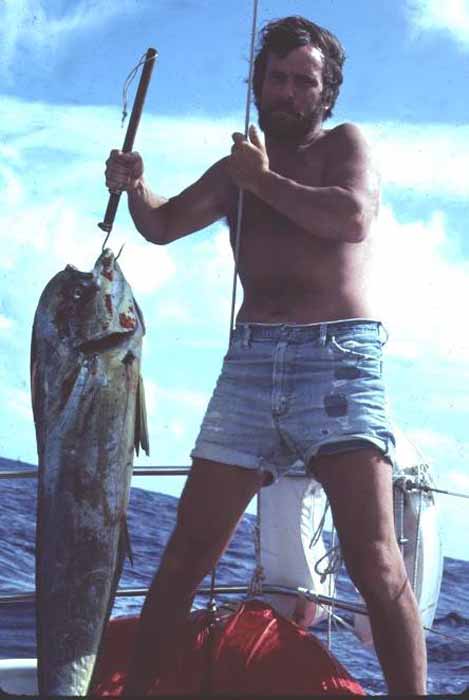

Wind is the sailor's friend; doldrums are good for mending sails, fishing and baking bread!

Only 20 days out of Cape May, the first near disaster struck when a defect in the oven caused a serious fire in the galley. When the crew had

covered two thirds of the distance to Cape Town, the Coast Guard ARGOS transponder malfunctioned

and went silent until reaching Cape Town. Some media outlets reported the crew "missing at sea."

During his circumnavigation, Marvin gleaned much additional knowledge about navigating by nature alone. He discovered that he could depend

entirely on the sun, moon and stars -- if they were visible. In overcast and stormy weather, he studied currents and wind patterns. But he

also found that the composition and color of the sea, cloud formations, the horizon, drifting objects and different types of birds or insects

were valuable sources of information. Creamer obtained his latitudes by identifying a star with known declination that happened to transit

through his zenith, directly overhead. After a lot of practice, he was just as aware of his longitude as was an eighteenth-century mariner,

so he had only to sail down a parallel of latitude for landfall.

On one occasion a squeaking hatch served as a navigational aid. Marvin had lost direction in a prolonged dead calm. With no visible stars

and currents to guide him, he could do little more than sit and wait. When the wind finally began to blow, a crew member moved the hatch

cover, which made a loud squeaking noise. Deductive reasoning told Marvin that dry air coming off the Antarctic had caused the squeak.

Moist air would have lubricated the track. Following the direction of the dry air, Marvin was able to get back on course.

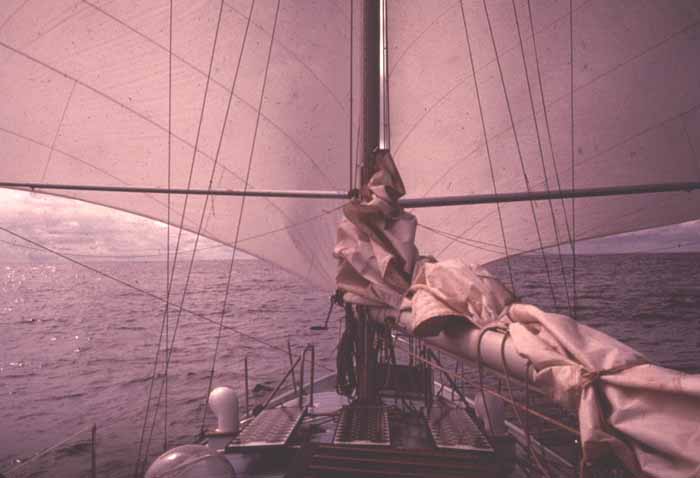

The brownish color in the photo below is from Sahara sand!

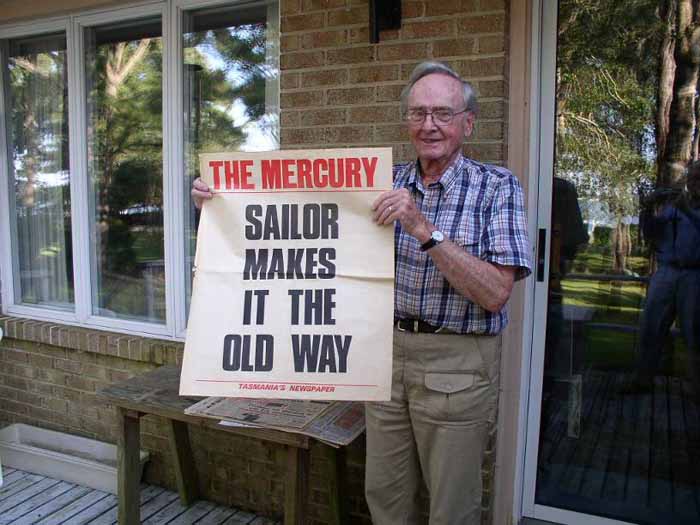

Arrival in Cape Town

The second leg from Cape Town to Hobart, Tasmania was 6800 nautical miles, accomplished in 77 days.

Six days out of Cape Town, the ARGOS transmitter failed a second time. There were two knockdowns in

40-foot seas. A crew member needed treatment for a bad salt water sore and frostbite, but the vessel

escaped damage on the rocky coast.

Fishermen greet the crew upon entrance in Tasmania

The Globe Star needs much TLC and must be fitted and tested with a new steering vane.

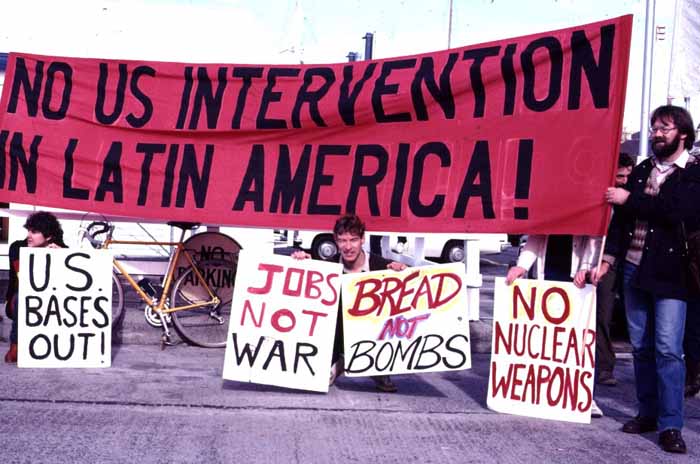

The locals gave Creamer a big welcome, but not all Americans!

From Australia to New Zealand was about 2000 nautical miles covered in 23 days of sailing. The

next leg was from New Zealand to the Falkland Islands was 5500 nautical miles in 53 days.

The final leg from the Falklands to Cape May was 7400 nautical miles in 98 days for a total of

29,460 nautical (33,870 statute) miles and 351 days at sea.

Falkland Islands

Lieutenant Commander Mark Stanhope (Royal Navy), captain of the submarine Orpheus. Stanhope was stationed in the Falkands

and asked Creamer to address all his men. Today, he is Supreme Commander of the British Royal Navy!

British Navy welders made an expert repair of the "indestructible" stainless steel tiller that had snapped in a storm.

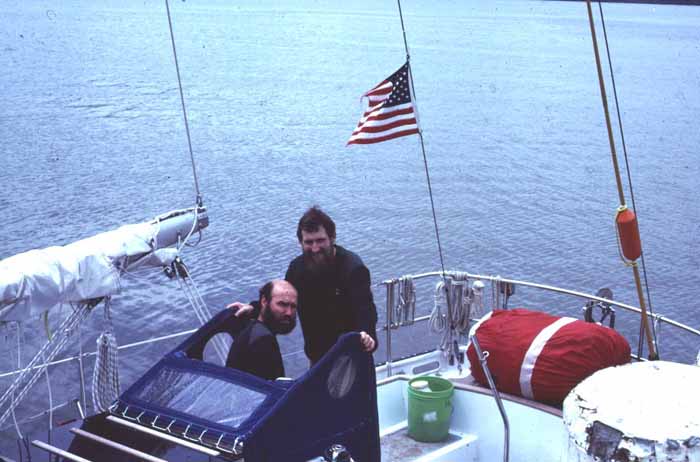

The following photos are not in a proper order, but I hope to correct this and add more comments soon!

Sightings of other ships were rare on the open sea, but in shipping lanes, there were some close calls.

After the Globe Star had passed the equator and the path of departure, Creamer's goal was accomplished.

A Coast Guard plane dropped packages for the crew in congratulations. Now they just wanted to get

home again!

On May 13, 1984, after 510 days at sea, Marvin Creamer neared the end of a voyage which had begun as a fantasy in his teenage mind.

A normal house fly which landed on the Globe Star hinted that he was about to become the first person in recorded history to

circumnavigate the globe without instruments. Victory was near!

Four days after the fly’s visit, following a night of wrestling with heavy sails, the exhausted skipper had just crawled into his

bunk when he was awakened by repeated shouts. Overhead, a U.S. Coast Guard chopper circled the Globe Star. Off the starboard bow,

Creamer spotted a red marker, the "F" buoy just 15 miles south of Cape May. At 1 p.m. on May 17, the Globe Star entered Cape May

harbor having logged 30,000 miles in 17 months, eleven and a half of those months at sea. Creamer wrote in his record of the journey,

"It has been a jolly romp!"

Using only environmental clues, Creamer had sailed around the globe in a grand feat of record-breaking proportions. Creamer proved

what he always believed, that it is possible to circumnavigate the globe in a small boat without instruments.

Creamer sails under the Twin Bridges on the Delaware to his victory celebration. Crowds awaited his arrival at Red Bank Park,

the point of departure 18 months earlier.

The soft-spoken 68-year-old retired geography professor became an American hero much admired by those he met during his adventure.

Creamer and his crew members docked at Cape Town, South Africa; Hobart and Sydney, Australia; Whangora, New Zealand; and Port Stanley

in the Falkland Islands. Christmas 1983 was spent in the Falklands where they unknowingly made port at a top secret British military

installation. "We were the talk of the Royal Air Force," Creamer writes. "They thought we were crazy, but treated us like kings."

"What we demonstrated," he concludes, "is that information taken from the sea and sky can be used for fairly safe navigation. How

far pre-Columbians sailed on the world's oceans we do not know; however, it is my hope that the Globe Star voyage will provide

researchers with a basis for assuming that long-distance navigation without instruments is not only possible, but could have been

done with a fair degree of confidence and accuracy."

Creamer has always been a doer as well as a dreamer.

|

|

|

|